Da me je strah?

9,99 € – 24,90 €

The novel Da me je strah? (Me, afraid?) transports the reader to the first years of World War II, a time of confusion, uncertainty, and historical shifts, and then leads them through the war, the first post-war year, and further, all the way to today.

Kresnik award shortlisted

Theatrical adaptation

Rights sold: Germany, Italy

Year of publication: 2012

No. of pages: 201

About the Book

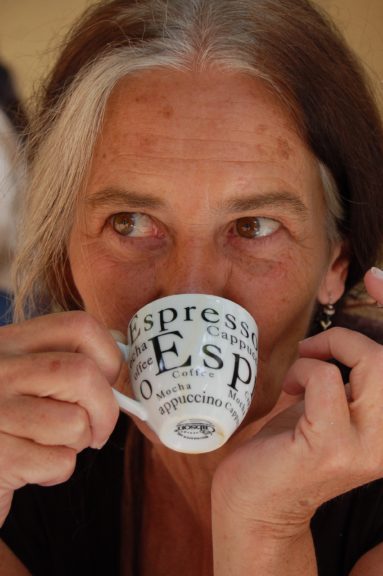

Maruša Krese was once asked in an interview: In the book All my Christmases we get to know you in different stereotypical female roles: mother, wife, daughter-in-law, housewife. Where is the female transcendence, the common denominator for all these roles? The author answered: I wouldn’t call it roles. I would call it woman. For that reason, and because her literature deals with women a lot, it is interesting to read Maruša’s first novel from this perspective.

At the very beginning we are faced with two voices: hers and his. Their inner monologues give us the broader picture (in part two they are joined by a third voice), while also revealing themselves. Because the perspective shifts evenly, they almost pass the ball to each other, which makes them easier to compare, especially as they’re often faced with similar situations.

It begins in the middle of the war, they’re both in the partisans. Both are caught in extremely harsh circumstance, both eventually questioning whether they’re not turning into beasts. But their thoughts and actions are very different. She can be roughly introduced thusly: she tries not to show any weakness, she faces physical challenges like a man, denies her femininity, she postpones her love for a man until after the war, she closes the eyes of the fallen, comforts, cheers up, denies herself sleep so that Ančka can sleep for longer; she supports Marija whose parents and sister are killed; she risks her life saving a horse from the water; when the men run she charges; when they’re surrounded her colleagues freeze, she runs through the hail of shots and even returns for her comrades; after the war, she is willing to sleep on the naked floor for months, have one dress and half a toothbrush; in politically uncertain times she visits a friend in Belgrade to offer her comfort. She faces everything life throws at her head on and fights it. I would rather die than run, she says. She is soft, often broken within, but hard, even sharp and cold on the outside. After the war, and despite all the obstacles, she realizes her great dreams: to graduate from university and see the sea.

He says, soon after the beginning: If I were wounded, I would immediately shoot myself. I believe this sentence defined the male characters in Krese’s writing. On first glance, it’s a noble sentiment, to not be a burden upon others when wounded, but more than that it signifies that when the going gets tough, he will retreat, run away. Of course many of his deeds are honourable – he protects her brother, takes on some tasks for his colleagues, makes sure her parents are safe, reads the classics in secret, saves books from the fires, is determined when other nations plan to stop fighting for Slovenes (In Bosnia we said no.); but he shows a different side as well – he steals brandy from the wounded; he delivers the news of Viktor’s death to his parents, then runs like a coward; when soldiers mock her and fill her backpack with rocks, he doesn’t take her side, but laughs along side the men; in partisan times he plans to build her a house by the sea, then puts it off; for years and years he tells himself he will visit his father in South America and then never does.

Other male characters are drawn in pastels. There are two notable extremes, some heroes, such as the harsh and arrogant commander Dušan, Lado who aims a gun at the teacher because of a bad grade, and on the other hand their son-in-law who is mainly a hippy, but refuses to be barefoot on his wedding and expects his father-in-law’s chauffeur to be available. The most obvious is definitely his father, who is notable through his absence. In many ways it’s a case of like father like son – when trouble starts, they would rather run than fight. They even see nobility in it. He, because he wouldn’t be a burden, his father because he went abroad to make a better life for his family.

A man who would rather run is, in the works of Maruša Krese, opposed by a woman who refuses to do so. And yet the author doesn’t glorify women. She grounds them and occasionally places them in the mud. It needs not be emphasised how they carry all four walls of the house, patiently suffer fatigue, and be the best of friends. They are strong, determines, willing to go beyond the limits of their body and will to achieve their goals. Being a woman is a duty. Yet they are always, from the day they are born, being limited by their antipode, the man. Or not the man as such, but patriarchy and its view of the world. That is why the duty of being a woman carries with it another duty – doing something for the woman. They fight for dignity and equality, which is strongly expressed in the right to an education. Her father would only allow his sons to visit school, never her daughter, because there is too much to be done at home – her mother and aunt fight for her right to an education. Similarly, after the war, she has to fight for her right to attend the university. In following their duty and their pledge, they sometimes walk over themselves, becoming hard, cold, sometimes even harsh and cruel, over the years. We follow her, whom men started to fear and think of as harsh, his mother who hides her pain and often hurts those around her (when she sees her granddaughter she comments: Nothing will ever become of this child.), even Marija who after many years, at the time of war in Bosnia in Herzegovina, calls from Belgrade in horror at the acts of her daughters who left to Sarajevo as volunteers. When Krese’s woman fights for her right to be gentle, she often inadvertently loses the ability to show gentleness on the outside. She doesn’t lose the ability to be gentle, but she often remains misunderstood and lonely, an eternal Antigone. But never is the focus on the tragic, Antigone in her deepest sense: I was born to join in love, not hate – that is my nature. She placed the imperative to be human first, despite the laws and the people calling her actions mad. Through such female characters, Maruša Krese, in her entire opus, subtly draws an image of a human being that we, living in a time when we are wolves to other people, need more than ever.

Stanka Hrastelj

Theatrical adaptation

Maruša Krese’s book was adapted for the stage by Prešern’s Theatre Kranj.